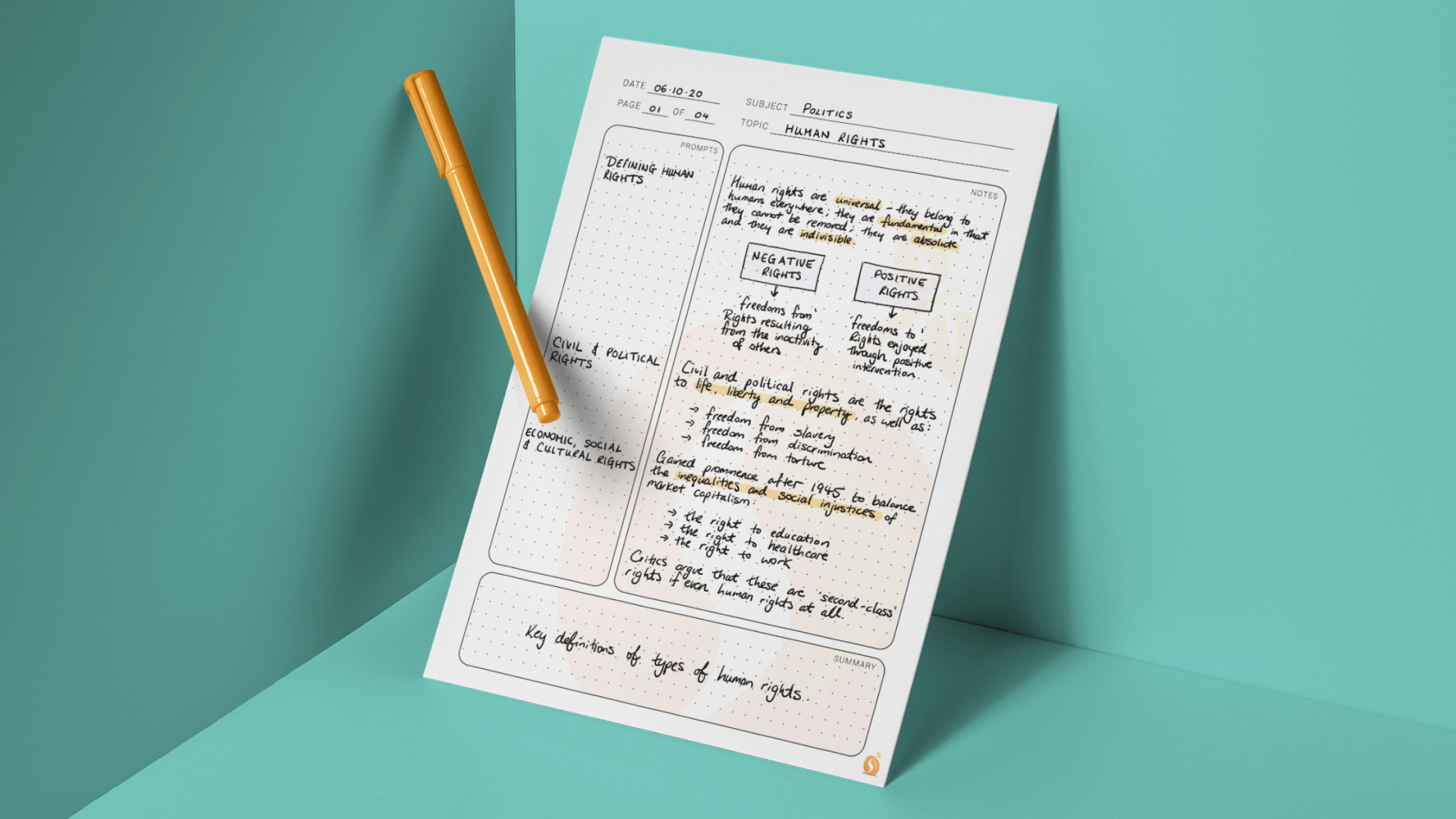

Inclusive Online Learning for Children with a Disability or Special Educational Need

Not an afterthought. Not an oversight. Accessibility is where we must begin.

In the UK, Northern Ireland has the highest disparity in educational attainment between students with a disability and students without a disability. This is not an issue that we can set aside to address later if online learning is set to continue to form part of our children’s education in September.

And it isn’t affecting a small minority either; one in five children in Northern Ireland has a disability or special educational need. By failing to be proactive in creating an online teaching framework that has the needs of all students in mind as the starting point, we are returning to a historical narrative that views barriers to education as an individual problem and not a societal problem.

If 2020 has taught us anything, it is the importance of community, care and togetherness. As a society, we are responsible for the provision of inclusive learning environments and equal opportunities for

all of our children.

The 2020 pandemic has forced primary and secondary schools to utilise online teaching methods

The closures of schools during the coronavirus pandemic has forced educators, children, parents and guardians to quickly come to terms with delivering and accessing online learning at home. Whilst online teaching methods have been widely utilised across universities, e-learning platforms and national tuition providers, they are a new experience for many children of primary and secondary-school age.

Nobody could have predicted the widespread disruptions that we would see for children’s education this year. As a result of this lack of warning and with no overarching education plan in place for online teaching, it is unsurprising that there has been a wide variation in the online teaching approaches that schools and other educators have adopted.

Across the board, schools and teachers must be strongly commended for their quick adaption to new and innovative methods of delivering lessons to their students beyond the classroom. The use of platforms such as Google Classroom for collaboration and the showcasing of students’ work on school Facebook and Instagram pages has enabled many children to continue to enjoy a peer-learning environment and a sense of school community whilst learning at home.

Many parents and guardians have indicated that online learning approaches have made them feel far more clued in to their child’s education as they can regularly see their engagement and feedback from teachers on day-to-day work. It provides a level of autonomy for students in providing them with some flexibility to choose when and how they carry out their learning tasks, as well as teaching good time-management skills when students must submit work online to their teachers by given deadlines.

As with higher education, online teaching has the potential to enhance the education of many children at primary and secondary level. It is likely that blended forms of education will be seen when schools return in September 2020, with some learning taking place in the classroom and the rest at home. Even well into the future, with robust systems of online teaching delivery in place as a result of this year, students who are off school for extended periods of time may benefit from being able to access lesson materials from their teachers in more engaging ways than the traditional method of physical learning packs being sent home.

It is very likely that some form of online teaching will become incorporated into future primary and secondary level teaching. This is a key, transformative stage within our current educational ecosystem. One thing that we must get right at this point - from the very beginning - is how online teaching for primary and secondary level children will be open and accessible to students with a disability or learning difficulty. This is not something that can be put to one side until it becomes a serious issue that should have been addressed in hindsight.

Educational barriers are a systematic problem - not an individual problem

To fully understand why educators must immediately prioritise online teaching methods for disabled students and students with learning difficulties, we need to take a step back in time to look at the history of how society’s understanding of disability has shaped the way in which institutions must be proactive - and not reactive - in enabling inclusivity and equality.

The Medical Model of Disability

Up until the 1970s, society’s view of disability was shaped by the medical model of disability. The medical model views disability as an individual problem - where something is ‘wrong’ with the individual and must, therefore, be corrected in order for the individual to have the same access to resources as a person without a disability could have. The language of the medical model underscores how it frames disability as an individual problem, with descriptions like ‘suffering from...’ and ‘needs’ and not being ‘normal’ all serving to emphasise that the issue exists only at an individual level.

Education under the medical model of disability separated students ‘with needs’ from ‘normal’ students in a clinical approach. Unsurprisingly, this served only to alienate and discriminate against any children that society deemed as ‘other’ to the mainstream system of education. Within the education system, a child’s disability or learning difficulty was treated as their main identity classification with, unsurprisingly, significant implications for their education, future employment opportunities and self-esteem.

The Social Model of Disability

In 1972, a letter was published in The Guardian newspaper by Paul Hunt, where he proposed the formation of a group for those ‘...in isolated and unsuitable institutions, where their views are ignored and they are subject to authoritarian and often cruel regimes’. This led to the formation of UPIAS (Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation), a disability rights organisation which led to a new model of viewing disability: the social model.

Under the social model, disability is viewed as a societal issue and not an individual problem. The barriers that a person with a disability or learning difficulty faces are not through fault of their own, but as a result of poorly designed institutions that are inherently discriminative. This shifted society’s view of disability completely.

According to the medical model, if a student was unable to access higher education because of a disability or learning difficulty, it was seen as an individual problem. The social model, on the other hand, views their barrier to accessing higher education as the result of a systematic failure in the education system to enable this opportunity.

How does this relate to online lessons and teaching virtually?

The disability rights campaign saw the introduction of legislation such as the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act 2001 and the Equality Act 2006. These laws sought to address institutional inequalities by making it illegal to discriminate unfairly against individuals because of a disability. In the education system, the onus was now placed on schools and educators to ensure that reasonable provisions were in place to provide disabled students and students with special educational needs with the same opportunities as those without a disability.

Section 13(1)(a) of the Special Educational Needs and Disability Act stipulates that ‘disabled pupils are not placed at a substantial disadvantage in comparison with pupils who are not disabled’ in relation to ‘education and associated services provided for, or offered to, pupils at the school'. This calls for the education system to take a proactive approach towards enabling inclusivity and equality for all students.

Although the very notion of online teaching through technology such as Google Classroom, Show My Homework and Zoom were not within the realm of possibility for legislators to consider in 2001, they have, as a result of the school closures, become an integral part of the education service provided by many schools and educators today.

If online teaching is to become integrated into the institution of compulsory education, proactive measures must be taken to ensure that it will not discriminate against disabled students or students with learning difficulties. 23% of pupils in Northern Ireland have a disability or a learning difficulty. The lack of any widespread precedent to follow is not a justification for taking a reactive approach to addressing the issues that could arise for disabled pupils when accessing online learning. We have existing research to follow on disabled students who have experienced issues with online teaching methods at university to be able to inform and guide our approach to online teaching methods now for younger students.

What do we already know from existing research on online learning?

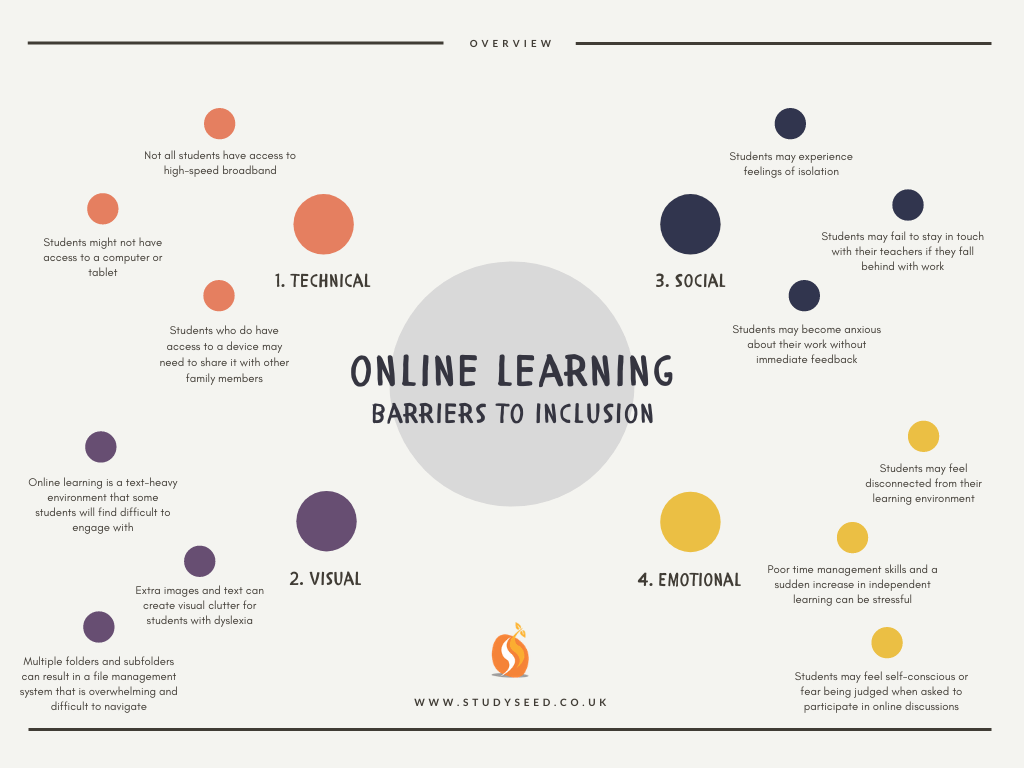

Existing research tells us that while it is not necessary for every teacher to be an expert in technology and digital accessibility, it is necessary for them to understand the barriers that students with a disability or learning difficulty may face when learning online. These barriers do not only include the existing barriers to learning that we can see in a traditional setting, but also the new barriers that online teaching methods can create. By being aware of the barriers, educators can create an online learning environment that enables their students to increase the efficacy of their technology and use of online learning platforms.

In a 2017 study (McManus et al.), interviews were conducted with adult learners with a mental health disability to explore the barriers that they face in accessing online learning at university. Some of the barriers that the participants discussed included feelings of isolation and a disconnect from the learning environment, along with the inability to receive immediate feedback from their educators. Many of the participants felt intimidated by the idea of participating in online discussions due to a fear of how they could be judged by other students or because they felt their contributions would look too simplistic in comparison to what other students had posted. They also felt that because they were learning at home, it was difficult to separate home life from their education - this was particularly exacerbated if family members did not fully respect or enable the time that they needed to be in ‘student’ mode while at home.

Another study by Shonfeld and Ronen - carried out over five years - followed a group of students completing an online learning course. They found that the average grades at the end of the course were higher amongst the students in the group with a learning disability. The study found that online learning provided students who were sensitive to loud or noisy environments with a quiet form of studying that was much more conducive to their preferences. It also enabled students who benefit from hearing information multiple times with the ability to replay their teacher’s audio as many times as they needed, as well as providing students with a shorter attention span with the ability to break their learning sessions up into shorter, more productive periods of learning.

An important element of online learning is self-regulated learning. In a traditional classroom setting, self-regulated skills come from observing the learning strategies demonstrated by educators, as well as being corrected and guided on the spot when encountering any areas of difficulty. Evidently, self-regulation methods must be conveyed in an altogether separate way when learning online. A study by Rice and Carter examined how well students were able to self-regulate when learning online. One of the key challenges that they found related to difficulties in communication - often, teachers would find it impossible to track progress if their students failed to respond to their messages. They noted that one way of mitigating this lack of response was to schedule their communication in advance - students were much more likely to check in with their teachers when given preset times to do so.

Another way in which teachers assisted students with self-regulation was through the use of pacing guides - these would give students an idea of how to pace their work and an understanding of how much work needed to be completed by set dates. However, the teachers went a further step here by creating custom pacing guides for students who had failed to follow the original timeframe. The purpose of the custom pacing guide was to show these students how they could catch up on missed work and get back on track with the original timeframe.

A 2012 study (Habib et al.) found that the design of online learning platforms can have a negative impact on accessibility for students with dyslexia. The students participating in the study noted that learning platforms often have a lot of clutter which creates an environment that is difficult to navigate. Features such as calendars, welcome pages, event information and additional writing on screen that isn’t directly related to the task at hand can make it difficult to focus on the relevant information. When accessing external websites for research, advertisements can add to the clutter on screen. Another aspect that can cause confusion is the use of subfolders - searching for information within folders is difficult if precise directions on where the educator has put a file has not been conveyed to their students.

'Accessibility is a term that has particular meanings in different contexts; here it refers to design qualities that endeavour to make online learning available to all by ensuring that the way it is implemented does not create unnecessary barriers...' (Cooper, 2006)

What methods can we use to make online learning more accessible?

One of the biggest challenges that online learning platforms pose is that they do not create an environment that is always conducive to the individual learning style that each student has. For example, students who have difficulty reading will find it extremely challenging to engage effectively with learning materials if these are presented mainly in written format online. Students who benefit from discussion and group activity will be at a disadvantage if there is no means of engaging with their peers within a virtual classroom. Kinaesthetic learners will find it hard to absorb new material if they are only able to engage with it visually on a screen.

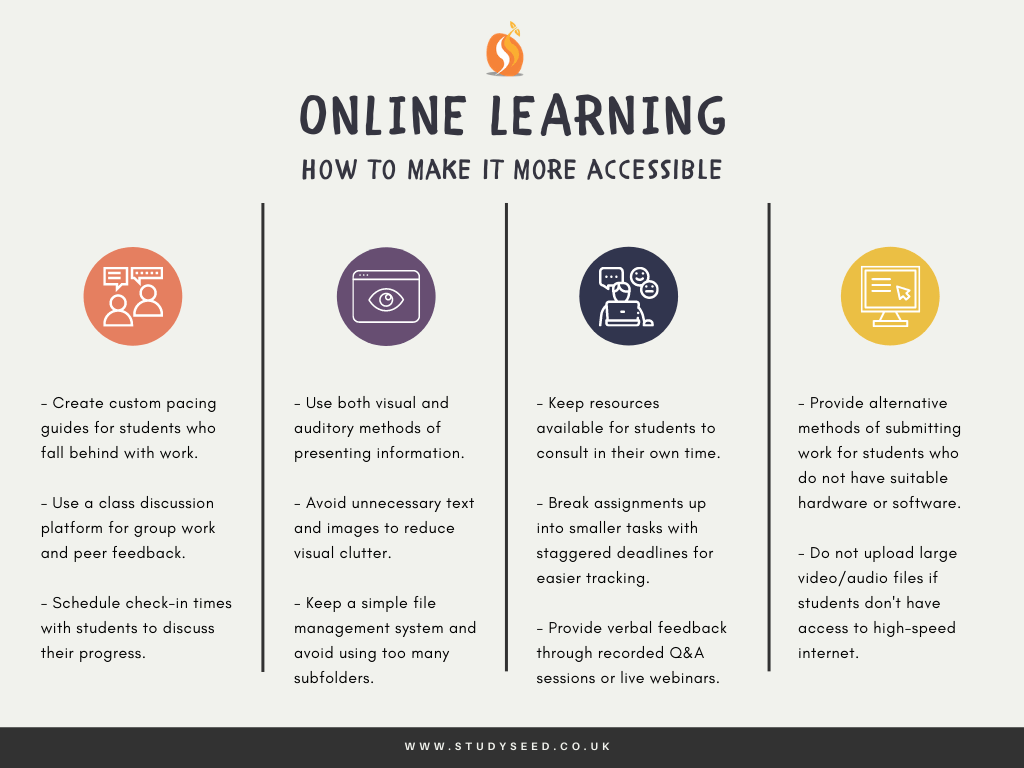

Given the existing research on online learning, the following are suggestions for educators to incorporate into online learning platforms, where possible, to increase their accessibility:

1. Use of both visual and auditory forms of presenting information.

Having a lesson available in written format, along with a video or audio recording of the teacher discussing the key points. If a video or audio recording is being used without a text file, then captions should be included.

2. Access to past resources should be kept available throughout the term.

One benefit of online learning is that it encourages students to consult previous lessons independently if they are easily accessed within the learning platform.

3. Breaking assignments up into smaller tasks with multiple deadlines.

Online learning provides an excellent opportunity for students to develop their time management skills and practice independent learning. However, for many students who are still developing these skills, large assignments with a set deadline for submission may be overwhelming and subsequently lead to a lack of engagement. By breaking larger assignments up into separate components with staggered deadlines, educators can keep track of their students’ progress and easily see if any students are not engaging with the material. Smaller deadlines will also encourage students to better develop their time management skills on a regular basis.

4. Custom pacing guides for students who have fallen behind with work.

By working with students who have not been able to meet the original deadlines for work, custom plans should be agreed upon that will guide students through catching up on work and getting back on track with the original schedule.

5. Use of a class discussion platform.

Students who benefit from group discussion and peer feedback will benefit from the use of an online discussion area within the learning platform. This is particularly important for students who feel isolated and demotivated by independent study outside of the classroom. However, it is also important to note that some students may feel anxious or self-conscious about being required to partake in online discussions if they do not feel confident in a topic or worry about asking a question in front of everyone that might make them look ‘silly’. For this reason, it is also important to have a means of communication where students can submit questions to the teacher that are not visible to everybody else in the class.

6. Pre-arrange check-in times.

Online learning does pose the risk of students failing to respond to queries sent to them - especially if they have fallen behind with work or failed to participate in tasks that have been set. Instead of relying solely on as-and-when communication between educators and students, each student should have a series of prearranged times each week/month when they must check in with their teacher to discuss their progress. Obviously, this requirement is not necessary if a system of blended learning is taking place with some lessons held in the classroom as well as online. However, for students who are not present in the classroom at all, a clear schedule of times to meet with their teacher online will help to mitigate against any communication issues that can arise when relying only on ad hoc communication.

7. Avoid unnecessary clutter and the overuse of folders and subfolders.

If it is possible to keep the presentation and organisation for files consistent across different classes, this should be done. Similarly, if it is possible to customise the landing page that students see when logging into their online learning platform, it is important to keep the displayed information simple, clear and relevant.

8. Verbal feedback through short Q&A sessions.

Many students may feel uncomfortable with asking questions in real-time in front of their classmates, but would benefit from receiving verbal responses to their questions rather than written feedback. One approach could be to encourage students to submit questions privately to the teacher and these could then be answered either in a live webinar or in an audio recording file that students can access in the learning platform. Verbal feedback sessions should be kept brief - mainly to engage with students who may find it difficult to concentrate through a longer session, but also to keep audio files small enough that they are still downloadable on slower bandwidths.

Sources and Further Reading

Cooper, M. (2006). 'Making online learning accessible to disabled students: an institutional case study', Research in Learning Technology, 14 (1), pp. 103-115.

Berghs, M., Atkin, K., Hatton, C. and Thomas, C. (2019). 'Do disabled people need a stronger social model: a social model of human rights?', Disability and Society, 34 (7), pp. 1034-1039.

Gallagher, D., Connor, D. and Ferri, B. (2014). 'Beyond the far too incessant schism: special education and the social model of disability', International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18 (11), pp. 1120-1142.

Habib, L., Berget, G., Sandnes, F.E., Sanderson, N., Kahn, P., Fagernes, S. and Olcay, A. (2012). 'Dyslexic students in higher education and virtual learning environments: an exploratory study', Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28, pp. 574-584.

Kotera, Y., Cockerill, V., Green, P., Hutchinson, L., Shaw, P. and Bowskill, N. (2019). 'Towards another kind of borderlessness: online students with disabilities', Distance Education, 40 (2), pp. 170-186.

Lambert, D. and Dryer, R. (2018). 'Quality of life of higher education students with learning disability studying online', International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65 (4), pp. 393-407.

McManus, D., Dryer, R. and Henning, M. (2017). 'Barriers to learning online experienced by students with a mental health disability', Distance Education, 38 (3), pp. 336-352.

Rice, M. and Carter, A. (2016). 'Online teacher work to support self-regulation of learning in students with disabilities at a fully online state virtual school', Online Learning, 20 (4), pp. 118-135.

Rodrigo, C. and Tabuenca, B. (2019). 'Learning ecologies in online students with disabilities', Media Education Research Journal, 62 (28), pp. 53-64.

Simoncelli, A. and Hinson, J. (2008). 'College students with learning disabilities personal reactions to online learning', Journal of College Reading and Learning, 38 (2), pp. 49-62.

Shonfeld, M. and Ronen, I. (2015). 'Online learning for students from diverse backgrounds: learning disability students, excellent students and average students',

The IAFOR Journal of Education,

3 (2), pp. 14-29.

Share this Article:

Join our Facebook community: